Unforeseen Ahead: Maria Hjelmeland

Perry McPartland

These

might just turn out to be exciting times for painters yet. One of

postmodernism’s most exciting leads is its allowance for the possible

appropriation of all past forms, without these forms bearing the defining

limits of their contemporaneous theory. And in so far as postmodernism

represents a critically theoretical response to theory, it most commonly

utilizes the past form as little more than locus and prompt. However in what is

more or less a reverse of contemporary habit, the 26 year old Norwegian, Maria

Hjelmeland, has chosen an involved engagement with the form of abstraction

while discarding the theoretical entelechy of its promulgation. Improvisory, a

seat-of-the-pants-sailing, insouciant, and sustained by a particular

virtuosity, her works of the last year bespeak a personal reformulation of

abstract painting.

Despite

the visual resemblance to the work of the Abstract Expressionists, Hjelmeland�s

paintings aren’t aesthetic mimesis or smug appropriation. Neither do these

distinctly female paintings spring from a criticism or even reaction to what

was a very male dominated field. Without a capitulation to its Spartan tenets

of style and purity on the one hand, and against any vicarious romanticism or

snide refereeing on the other, she simply gambles her talent- and proceeds

unforeseen. Regardless of the familiarity of their form, these paintings’

character and implication are idiosyncratic and fresh, a singular sensibility

emerges that sustains them as genuine works.

To

describe them is to

style=’mso-bookmark:OLE_LINK7′>iterate their diversity and

invention. From the fifteen paintings I have seen, seven distinct and original

abstract styles emerge. And this isn’t the dabbling of mere precocity-rather,

each picture exhibits a mature resolution. Furthermore, it seems to me that it

is through their discrete diversity that their sense is revealed. They are

foremostly visual, highly colored and materially diverse. Not usually large,

they nonetheless have a forthright physical insistence, the surety of their

material handling asserting itself. It is through this touch- as opposed to any

stylistic consistency- that the artist’s signature and the work’s personality

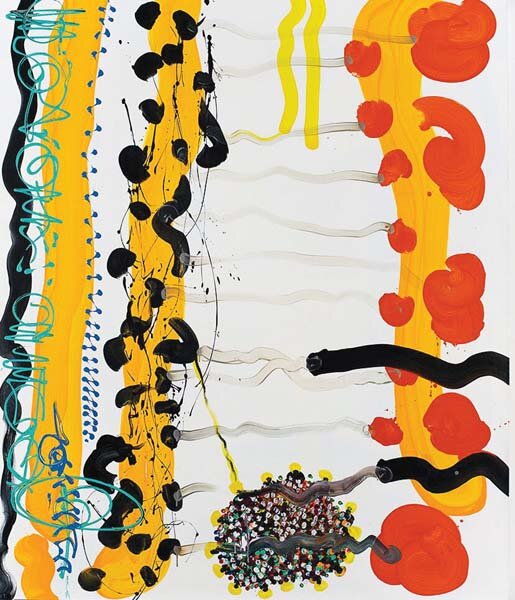

are manifested. In Untitled 7 (2003), the paint lumps, dribbles, swerves gravidly,

streams and thickens. A saturated vermilion makes a brazen slash across

patchwork tones and over a puddled pool of glue, jumping at its combed,

extrovert edges. An A3 sheet of luminescent orange rice paper is wrinkled,

folded, torn and fingered into the paint surface, while the canvas itself is

creased, scored and punctured, further large cuts of canvas are sown back into

the surface. And as a simultaneous arrest and coda, an ochre line of masking

tape guillotines the action and gives the painting an edge 2 inches before its

bottom proper.

A

vigorously chromatic palette is most usual, though experimentation being the

only norm, the palette can shift to the tautly tonal, or even to the lights of

pastoral calm. Aesthetically they are very alluring. Yet Hjelmeland�s balances

her natural flair for the beautiful with a certain intelligence and taste.

While the coloring is measured and seductive- taking its pointers from 19th and

20th century tradition- it has been extended to include the bold and glaring

hues that characterize design and pop art. Acid yellows bee-striped with an

oily liquorice-blue, chocolate mousse splurges pitted with tart pink paw

prints. The moments of elegy that abstraction naturally lends itself to are

visually qualified, or otherwise interrupted by the vulgar or cartoonish-

sometimes even a caustic bite from the Pattern and Decoration Movement.

Contrary

to the majority of Abstract Expressionists, these pictures possess a rare

quality of mood (my feeling being that the greater amount of Abstract

Expressionist work was characterized by sensation as opposed to mood- a big

difference). And although Hjelmeland’s work is likely to strike the viewer as

initially sensational, it has none of Abstract Expressionism’s sublime angst or

its gruellingly necessitated and final quality of image. In her defense, the

mythic and heroic proportions that this implies are probably quite foreign to

Hjelmeland’s sensibility- her resources having their basis in prodigal flair

and quick invention. The voice here is whispered, acute and pudent; as objects

they are intimate and mutual. Rothko said big paintings, in so far as they wrap

around the viewer, are intimate. However that’s a different intimacy- the

sensation of being enveloped completely in their environment. Hjelmeland’s

works, the small pieces in particular, often have the close presence of a

person.

This

mood of theirs is often informed by an unusual spatial quality. Lots of the

works- even some of the square images- tend to encourage a lateral reading,

which engages the eye in such a manner that they seem to take to ages to

traverse; they feel

much longer than they are. It’s a quality to be found in Vermeer and some of

the less overt Twombly’s, and it makes for a lightness and a rare,

contradictory limbo.

There

are some things that her work needs, but these present limitations are the

natural limitations of her short time with the medium. And I’ve decided to

withdraw before suggesting them- the absence of a Thou shallt having so

far been revealed as beneficial, perhaps even formulatingly definitive of her

process.

The

exigencies of painting being so strenuous, and the line that marks quality so

high, any assessment of a young painter can only be provisory. In Hjelmeland’s

case we can only collate and remark: a hazard of natural talent and a

personality of singular invention. And we can keep an eye on her.